The ‘crowdy three’ – a conceptual model of how supply chains can (should) act as development initi atives (i.e. be ‘ethical’)

Note: This post is derived from the joint work of Dr Daniel Gregg and Dr Daniel Hill in relation to mechanisms for market-based programs to act as effective development initiatives. You can see more at www.heuris.com.au.

Note 2: This is a longer post…

Value chain development remains a key tool to achieve socio-economic objectives in rural areas of all countries. Yet value chain development at scale is difficult. Bulk commodity supply chain programs remain low-value for participating farming households on average, undermining potential improvements in revenue for smallholder farmers and economic benefit for source countries. Overall quality, even of the growing array of ‘specialty’ commodity programs in, for example coffee and cocoa, remains low despite the promise of ‘relationship trade’ models and the growing range of certification standards supposed to increase value to smallholder farmers. Even when these specialty programs generate increased value there is increasing evidence to show that they fail to do so in a way that benefits target households (i.e. they do so for the ‘elites’ in a community, rather than for poor households most in need of income improvements).

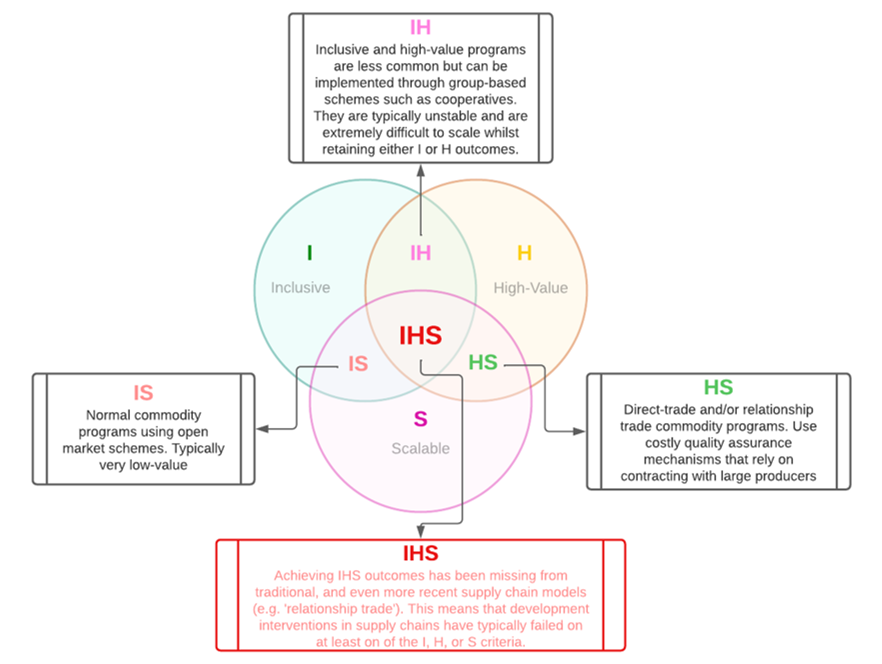

We introduce conceptual, and pragmatic, solutions to these issues. The core problem facing achievement of high-value and financially sustainable smallholder inclusive value chains (SIVCs) is conceptualised as needing simultaneous achievement of three outcomes that tend to crowd each other out in traditional supply chain models: (1) value to participating farming households; (2) inclusivity (effective pro-poor targeting for participation), and; (3) scalability (the program is able to substantively impact on national-level welfare outcomes). We term these three concerns the ‘crowdy three’. The presentation includes conceptual foundations, evidence and operational aspects for supply chain interventions, planned research in the near future to improve welfare impacts from value chain interventions, and future extensions.

Poverty and the role of ‘value chain upgrading’

Extreme poverty, measured by the number of individuals living below $1.90 US dollars a day, remains high at 689 million people (World Bank, 2020). There is an increasing consensus that economic growth is insufficient in alleviating poverty where inequalities often prevent the poorest and most marginalised accessing the benefits of economic growth.

It is recognised that improving the welfare of rural communities who depend on agriculture is the most important goal in global poverty alleviation. However, modern agricultural supply chains have evolved over the last 20 years due to worldwide income growth, technological change, urbanisation, economic liberalisation, and globalisation. Evidence suggests that this evolution has made smallholders and poorer rural communities more vulnerable to volatile prices and has favoured power imbalances in supply chains where rents are extracted to downstream retailers and processors.

Given these concerns with modern agricultural supply chains, Value chain upgrading processes are increasingly being promoted as an intervention framework for rural development.

Value chain upgrading is the process of improving the competitiveness of the value chain by improving product quality and production efficiency, or changing value chain functions, governance or end markets (Humphrey and Schmitz 2002).

Value chain upgrading can be complementary to broader development where processes seek to organise and support the livelihoods of smallholders and other value chain participants (Kelly et al. 2015), whilst providing mutual benefits for downstream value chain participants.

The emergence of value chain upgrading has occurred in parallel with the evolution of agricultural supply chains. Firstly, rural communities are increasingly exposed to public and private standards or food quality and safety to access new domestic and export markets. Investments are also being made by modern retailers and processors in transitioning economics to meet new demand segments - known as the “Supermarket revolution” (Barrett et al. 2020). These retailers and processors have increasingly sought greater vertical coordination in the supply chains by more closely engaging with smallholders through contract farming or outgrowing schemes. Finally, increasing incomes and preferences in high value markets are seeking assurance over social and environmental traits in the products they consume, increasing the incentives of private businesses to engage in accreditation schemes such as Fair Trade and Rainforest Alliance.

Increasingly value chain upgrading is being considered as a more direct vehicle for rural development outcomes. Value chain upgrading has been adopted by organisations such as the FAO (Kelly et al. 2015) and UNDP (2015), and represents a key focus area for large NGOs (Oxfam-International 2019) and ACIAR (2020). Smallholder dominated, export orientated value chains, such as coffee, cocoa, vanilla, and other tree crops have received particular attention in value chain upgrading processes given production is closely linked to a large number of poorer communities (Vicol et al. 2018, Ros-Tonen et al. 2019).

Value chain upgrading in smallholder dominated value chains is often achieved through differentiation along product attributes based on quality, ethical or sustainable “content”, which has increasing global demand in more developed countries (Ponte 2002, Reardon et al. 2009). Value chain upgrading processes can seek to provide market access and new economic opportunities for smallholders and poorer rural communities in these niche markets, thereby contributing to development outcomes through potentially higher incomes and reduced risk.

Empirical evidence suggests many value chain interventions fail to achieve goals

A significant number of studies have considered whether value chain upgrading processes provide broader development outcomes for rural communities (see Oya, 2012, Ton et al. 2018, Bellemare and Bloem 2018, Oya et al. 2018 and German et al. 2020 for a review of this literature).

However, evidence suggests that value chain upgrading is often strongly associated with ‘elite capture’ wherein wealthier and/or more socially powerful households are able to capture opportunities more effectively than poorer households (Vicol et al. 2018, German et al. 2020). Whilst these households are often able to derive value from participation through higher incomes or new market opportunities, this value is concentrated only within a few households who are relatively well off.

In some cases value chain upgrading avoids this elite capture issue, but the value of participation in terms of average income have been shown to be lower (Ton et al. 2018). In the literature, this has been defined as adverse inclusion, where the participation of smallholders in a value chain leads to low or diminishing returns due to unfavourable terms of engagement (Herrmann and Grote 2015, Ros-Tonen et al. 2019). In other cases adverse inclusion in value chains can be related to other aspects of welfare such reducing women’s empowerment, exposing smallholders to additional risk, or trapping households in cycles of indebtedness (German et al. 2020).

A significant number of studies have considered whether value chain upgrading processes provide broader development outcomes for rural communities (see Oya 2012, Ton et al. 2018, Bellemare and Bloem 2018, Oya et al. 2018 and German et al. 2020 for a review of this literature).

However, evidence suggests that value chain upgrading is often strongly associated with ‘elite capture’ wherein wealthier and/or more socially powerful households are able to capture opportunities more effectively than poorer households (Vicol et al. 2018, German et al. 2020). Whilst these households are often able to derive value from participation through higher incomes or new market opportunities, this value is concentrated only within a few households who are relatively well off.

In some cases, value chain upgrading avoids this elite capture issue, but the value of participation in terms of average income have been shown to be lower (Ton et al. 2018). In the literature, this has been defined as adverse inclusion, where the participation of smallholders in a value chain leads to low or diminishing returns due to unfavourable terms of engagement (Herrmann and Grote 2015, Ros-Tonen et al. 2019). In other cases, adverse inclusion in value chains can be related to other aspects of welfare such as reducing women’s empowerment, exposing smallholders to additional risk, or trapping households in cycles of indebtedness (German et al. 2020).

Scalability, the third element of value chain upgrading is rarely discussed in the literature. Part of a reason for this is because the focus has often been on large supply chain actors that use contract-farming mechanisms to secure quality in the supply chain. In these cases, scalability is largely fixed. However, our interest is in achieving value chain upgrading interventions that are substantive as development tools: that they generate globally or nationally meaning achievements against SDGs. This will often mean the use of programs that can scale outside of traditional forms of oversight.

Value chains may both be inclusive and provide value for participants but, because increasing cost of maintaining relationships across member bases to provide assurance over product quality, these value chains tend to be uncompetitive as they scale without external funding from development programs or Governments. The governance of these value chains also tends to be unstable, meaning that as these value chains scale, they either tend to fail in terms of inclusion (i.e. trend towards elite capture) or value (adverse inclusion). This is driven both by local elite capturing the benefits from value chain upgrading (e.g. Vicol et al. 2018), and where ownership and governance of value chains becomes increasingly concentrated to larger firms who increasingly seek to reduce contracting costs (German et al. 2020). Platteau (2009), for example, argues that the act of decentralising governance of aid projects, including supply chain programs, involves large trade-offs with the other objectives of maintaining high-quality (and thus high-value) and inclusivity (as elite capture controls are eroded). The complexity of establishing decentralisation under standard approaches to development programs such as traditional supply chains is shown by Platteau (2009) to be such that scalability is a ‘hard’ problem for development programs.

Note: We have a paper published on this topic – see Hill, D. Gregg, D. and Baker, D. “Trading off inclusion, value, and scale within smallholder value chains”. World Development, 191: 106973.

The crowdy three problems in achieving development objectives through value chain upgrading

The issues around elite capture, adverse inclusion and scalability directly relate to three main underlying factors that are required for value chain upgrading to be an effective vehicle for development outcomes. These are:

Value: Value chain upgrading activities must generate meaningful income increases for participants accounting for the additional effort/cost that may be required for participation. Value may also consider other benefits from participation beyond incomes that are valued by participants, such as assurance over price, and other support services such as financial management and agricultural extension.

Inclusivity: The inclusive factor relates to the distribution of value across the rural community. An inclusive value chain has limited barriers to entry for anyone seeking to engage with the value chain. Inclusive value chains will have broader engagement with smallholders, women, youth, and those without land, rather than focusing on larger farmers.

Scalability: A scalable value chain upgrading activity is one that can grow and support more people over time in a way that is sustainable. This requires the value chain to remain financially self-sufficient, have effective governance structures and remain competitive for end markets.

We have summarised these factors as the ‘Crowdy Three’ because reviews of the literature show that one, or sometimes two, of these factors can be solved using traditional value chain upgrading models but not all three at once – our review shows that, at least for traditional supply chain models that ‘three is a crowd’.

Which pathway is most promising to overcome value chain failures?

There have been many value chain programs that appear to have achieved high-value (but not I or S), or inclusivity (but not H or S) and even some that have temporarily achieved some value (little ‘h’ instead of big ‘H’) and some inclusivity (little ‘i’ instead of big ‘I’). There may even be very few programs that can truly be claimed as being IH (both high-value and inclusive). Whilst these are rare, achieving quality improvements through contracting is not considered a ‘hard’ problem, at least at small scales.

On the other hand, Platteau’s (2009) critique suggests that scalability (S) is a hard problem. And yet the most common supply chain program in existence, open market procurement systems, has repeatedly solved the scalability problem. Not only have open market systems solved the scalability problem but they are, essentially by definition, inclusive. Open market systems are thus true IS systems. Where open market systems fail is in their achievement of high-value. Much of the crowding out conceptualised in the Crowdy Three model relates to the avenues sought in traditional supply chain models to achieve high value. These avenues involve mechanisms that take a one-eyed view to provide assurance to supply chain actors around quality in order to moderate the tendency of open market systems with difficult quality monitoring to devolve into ‘markets for lemons’ (Akerlof 1978). This narrow view of the problems facing value chain upgrading as a development tool means many of these programs trade off wins against the ‘hard’ problem of scalability, and often of inclusivity, in order to generate a high-value supply chain.

Given the available evidence, there are three main avenues to solving the Crowdy Three problem:

Take the IH route and seek innovations that allow scalability: this means identifying the very few value chain interventions that are both I & H, generalising their conceptual foundations, and seeking innovations that can ‘fix’ the hard problem of scalability

Take the Hs route (scale is achieved in volume, not in participation) and seek to make increase inclusive participation (I and move s to S): this means solving two major problems at once. Achieving scale in terms of volume is often easy enough when enough large producers are present (or one very large producer). Inclusivity is only achievable when you have high levels of participation, however. This route is unlikely to yield effective outcomes for achieving SDGs unless alternative policy instruments are used (e.g. redistribution)

Take the IS route and seek innovations that allow increasing value: this means adapting existing and well-known open market systems to better incorporate avenues for quality differentiation and appropriate payment for efforts toward quality. It may also involve innovation in procurement systems that seek to allow greater participation in non-farming components of the supply chain (e.g. harvesting, processing, marketing, procurement).

Which route seems the most promising?

We view option 3 as the most promising. Quality concerns are a well-known conceptual issue in economics with a wide range of mechanisms to deal with them. The most obvious of which is contracting for quality (explicit payment contracts for quality). The only innovation needed in that case is an efficient, effective, and trusted quality assessment mechanism along with a contract structure that rewards efforts toward quality improvement sufficiently. This is the basis of our Smallholder Inclusive Value Chains program.

Asymmetric information problems are central to solving the Crowdy three via the IS route

Asymmetric information is prevalent over hard-to-observe traits in production outputs. These can include product quality in quality-focused value chain upgrading (e.g. the quality of coffee cannot be observed at time of purchase), or other important credence attributes such as social and environmental factors in production. Producers face costs to produce higher quality outputs, and quality monitoring typically occurs on an aggregated basis by downstream firms. This creates free-rider incentives, where individual producers face incentives to lower the quality of their own produce and pass it off as higher quality in order to take advantage of low levels of quality monitoring at an individual level. These incentives lead to a lowering of quality incentives over time and an associated reduction in aggregate quality. This is the typical race to the bottom outlined in the classic Akerlof (1978) “market for lemons” summarised below, and means that participants in these value chains face low value from participation even if barriers to entry are low.

Figure 2: Akerlof’s (1978) “Market for Lemons”

Value chain upgrading typically seeks to resolve these unobservable quality attributes to access new markets, albeit by trading off inclusivity objectives to maintain the financial viability of incentivising quality. To observe traits such as quality or credence attributes, procuring firms face substantial quality monitoring costs under standard approaches to quality measurement. These transaction costs include monitoring programs over production and outputs to provide assurance over hard-to-observe traits, and monetary incentives to the producers for repeated contracting over time. To minimise transaction costs, monitoring programs in high-quality value chains ubiquitously involve contracting with a smaller number of larger primary producers and lead firms.

This ‘relationship’ approach to overcome information asymmetries has been widely leveraged across commodities, such as contract farming in horticulture (Ton et al 2018, Bellemare and Bloem 2018) to relationship-based coffee value chains (Vicol 2018). It is often claimed as an ethical approach to contracting, but the evidence and theory indicate create elite capture concerns because the incentives for lead firms are to engage with a smaller number of larger and better-connected farmers (Ton et al 2018, Vicol 2018). Farmers may also face upfront transaction costs to participate in these value chains (e.g. invest in higher quality production processes) or face non-monetary barriers to entry such as exclusion from farmer cooperatives, which reinforces the elite capture problems with relationship approaches.

For value chain upgrading to be an effective vehicle for development outcomes in rural communities, the trade-off between information asymmetry and transaction costs needs to be resolved.

The Smallholder Inclusive Value Chains (SIVC) project

The ‘Smallholder Inclusive Value Chains’ (SIVC) project is a trial program that has been operating since 2018 that seeks to generate substantial value from accessing, at scale, high-value coffee markets for Ugandan coffee farmers. The program involves a novel digitisation, governance, and procurement regime that has been proven to generate substantial value improvements for export coffee and that achieves very high levels of inclusivity of smallholder farmers, women, and youth.

The objectives of the trial program are to jointly:

Develop a supply chain program that can achieve the ‘crowdy three’ targets of inclusivity, high-value, and scalability via the IS route, and;

To do so whilst meeting standard private-sector business targets including maintaining margins within the supply chain;

To do so in a way that enabled the creation of a coffee program that leverages existing institutional infrastructure including the cooperative unions, growers associations and the coordination of those through the National Union of Coffee Agribusinesses and Farming Enterprises (NUCAFE).

The trial program has been running for 4 years, doubling in scale (or more) each year and has generated a range of business and social value targets including:

Value to farmers: an increase in value to farmers of, on average, 20%-40% compared to normal market prices. This is equivalent to an increase in income worth over 1.5 months of normal labour and enough to send a child to school for an entire year.

Value retention in Uganda: An increase in the value of coffee sold of 148% compared to the average Arabica coffee sold in Uganda and of 49% compared to the highest-grade Mt Elgon Arabica coffee sold in 2021.

Smallholder focus: An average accepted lot size of approximately 50kg (an amount that can be harvested by one individual within ~3 hours) and a very high number of contributing farmers per tonne of equivalent green coffee (~30 farmers per tonne) compared to other high-value coffee programs currently in operation.

Inclusivity: Over half of the volume of accepted coffee provided by youth and women.

Scalability: Operating a distributed network of buying agents that require no capital and for which governance issues are essentially non-existent (safety, financial accountability).

Financial sustainability: A proven business model that is financially sustainable.

Whilst the trial program has generated proof over the validity of claims regarding inclusivity and value there remains a need to integrate all factors into a program that can achieve national-level scalability, and to do so in a way that includes not only land-owners but also the landless poor and youth.

Remaining gaps and next steps

There are a number of steps remaining to turn the Uganda pilot program from a pilot into a full-scale national SIVCs program. These include:

Testing the program across regions to consider governance scalability issues such as outlined in Platteau (2009)

Innovating in procurement systems to facilitate:

Governance and quality assurance across wide regions

Coordination in the supply chain to ensure quantity and quality targets are met

Enablement of a micro-enterpreneur ‘ecosystem’ to support the program

Enhancing traceability

Increasing digitisation to reduce the need for in-person oversight and payment systems

In addition we are interested in seeking to increase the impact of financial transfers made in this program. Recent work (Cansin et al. working paper) for example, shows that income transfers often do not lead to large welfare gains due social and kin ‘taxation’ (unwelcome transfers). Our research program is seeking to gain insights into:

How to maintain and increase pro-poor outcomes through inclusivity targeting mechanisms

Options to increase the rate of transfer from income to household savings and productive investment, including

Behavioural/nudge type interventions

Options to adjust payment approaches within the supply chain itself (e.g. over an annuity instead of a lump sum, a perpetuity option akin to superannuation, a distributed payment system, and more)

Broadening the supply base whilst improving inclusivity

Increasing supply chain resilience by seeking to enable a ‘micro-entrepreneue ecosystem’ that undertakes all supply chain activities (instead of us organising those)

Setting up as a national program

References

ACIAR 2020. ACIAR Annual Review 2019-2020. Canberra, Australia: ACIAR.

Barrett, C. B., Reardon, T., Swinnen, J. & Zilberman, D. 2020. Agri-food value chain revolutions in low-and middle-income countries. Journal of Economic Literature.

Bellemare, M. F. & Bloem, J. R. 2018. Does contract farming improve welfare? A review. World Development, 112, 259-271.

German, L. A., Bonanno, A. M., Foster, L. C. & Cotula, L. 2020. “Inclusive business” in agriculture: Evidence from the evolution of agricultural value chains. World Development, 134, 105018.

Herrmann, R. & Grote, U. 2015. Large-scale agro-industrial investments and rural poverty: evidence from sugarcane in Malawi. Journal of African Economies, 24, 645-676.

Humphrey, J. & Schmitz, H. 2002. How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional studies, 36, 1017-1027.

Kelly, S., Vergara, N. & Bammann, H. 2015. Inclusive business models. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Oxfam-International 2019. Fighting inequality to beat poverty: Oxfam International annual report 2018-19. Nairobi, Kemya.

Oya, C. 2012. Contract farming in sub‐Saharan Africa: A survey of approaches, debates and issues. Journal of Agrarian Change, 12, 1-33.

Oya, C., Schaefer, F. & Skalidou, D. 2018. The effectiveness of agricultural certification in developing countries: A systematic review. World Development, 112, 282-312.

Ponte, S. 2002. The latte revolution'? Regulation, markets and consumption in the global coffee chain. World Development, 30, 1099-1122.

Reardon, T., Barrett, C. B., Berdegué, J. A. & Swinnen, J. F. M. 2009. Agrifood Industry Transformation and Small Farmers in Developing Countries. World Development, 37, 1717-1727.

Ros-Tonen, M. A., Bitzer, V., Laven, A., de Leth, D. O., Van Leynseele, Y. & Vos, A. 2019. Conceptualizing inclusiveness of smallholder value chain integration. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 41, 10-17.

Ton, G., Vellema, W., Desiere, S., Weituschat, S. & D'haese, M. 2018. Contract farming for improving smallholder incomes: What can we learn from effectiveness studies? World Development, 104, 46-64.

UNDP 2015. Realizing Africa's wealth: Building Inclusive Businesses for Shared Prosperity.

Vicol, M., Neilson, J., Hartatri, D. F. S. & Cooper, P. 2018. Upgrading for whom? Relationship coffee, value chain interventions and rural development in Indonesia. World Development, 110, 26-37.

World Bank 2020. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune. Washington, DC: World Bank