Quality assessment innovations for at-source procurement

Coffee quality assessment is something that speciality coffee supply chain actors know intimately. Identification of a range of issues in agronomy, processing, and roasting of arabica coffee is epitomised in the ‘Q-grader’ initiative (see here) and in the parameters set by the Speciality Coffee Association (www.sca.coffee). Most of this quality assessment comes at the finished green bean stage or after roasting. There remains little in the way of formal quality assessment mechanisms for early stages of the coffee supply chain.

Key characteristics of the early stages of the coffee supply chain (in smallholder dominated settings) include:

Households using labour (household or employed labour) to pick coffee trees

Sale of both ‘fresh’ coffee cherries and semi-processed coffee (called ‘parchment’) by households to ‘middlemen’, buying agents and processing stations

It is difficult to assess quality of parchment coffee without completing processing, roasting the coffee and cupping it. As a result, there is a ‘market for lemons’ problem in localised parchment coffee markets (see our ‘good intentions…’ post here)

Assessing quality of freshly picked coffee cherries is relatively straightforward:

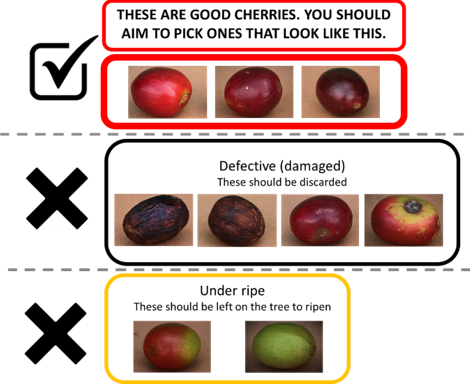

All berries should be red in colour across the whole fruit

Holes or insect damage is indicative of major faults that can severely impact on flavour even at a low proportion of accepted coffee

Yellow or green cherries impact negatively on flavour but typically have limited impact in terms of generating ‘bad’ flavours

But, there are also constraints to assessing quality of fresh coffee

There are up to 100,000 coffee berries in a 100 kilograms of freshly picked coffee meaning that it is essentially impossible to adequately assess a whole ‘lot’ of coffee being submitted for quality assessment

Coffee is sold by weight and ‘selective’ picking of red cherries takes more time (cost) so:

There is an incentive for sellers to pass off lower quality coffee as high quality (e.g. by hiding unripe/damaged berries below red berries in a bag)

Contracting for ‘selectively picked’ coffee only (i.e. undamaged ripe berries) requires additional compensation relative to non-selective programs

Ostensibly, commodity programs do undertake quality assessment but this is highly subjective, takes a lot of effort and is generally entirely unable to discern average quality coffee from good quality coffee lots.

Our research on quality

Our early research in this project was focused heavily on being able to obtain high quality fresh coffee on the open market (i.e. in a way that maximises participation from all actors).

Our discussions with local growers and buyers tended to indicate that the ‘fault’ of low quality coffee was with the pickers (along the lines of “we tell them to pick red but they don’t know how”). This indicated that locals thought the main problem was one of education. However, we viewed it as a lemon-market problem wherein there was no incentive for any actor to pay more for high quality coffee because their upstream buyers would not pay more. The result being that pickers were not incentivised to ‘pick red’. Another reason we had this view over the ‘education’ view is that it was obvious that picking red was less a cognitive issue (‘how’ do we pick red) and more of an effort-reward issue (‘why’ should we pick red when we are not paid for that).

We worked through three main options to consider these possibilities, and the option to post-harvest sort coffee to obtain high quality coffee on an open market supplied by many smallholders:

‘Teach’ pickers to ‘pick red’

Contract pickers/growers to pick red

Post-harvest sorting of coffee into a ‘high-quality’ lot and a ‘low-quality’ lot

To test these options we simultaneously ran two field experiments to both test basic theories on incentives/education and to consider options for generating high-quality coffee outputs we ran a contracting experiment with coffee pickers testing:

The role of quality incentives alone for ‘picking red’ (i.e. if they passed a quality test they received a bonus)

The role of ‘education’ on ‘picking red’ alone

Both (1) and (2)

Our results from this contracting experiment showed that we could obtain very high quality outcomes from doing (1) alone – i.e. by contracting for quality. There was no ‘education’ issue – pickers just needed to have an incentive to spend more care in picking. Education played a small role in the first tests, but these effects were quickly dominated by incentivised contracts.

We also tested post-harvest sorting of coffee for ‘normal’ coffee bought on the open market:

After buying ~50kg of coffee six of us sat down with tarpaulins, basins, etc. sorting the red berries from the yellow/green ones and the damaged ones. After 2 hours we were less than halfway through the 50kg lot. Clearly, post-harvest sorting was not feasible without massive investment in technology/capital (see here why that is not of interest to us - Economic concepts in smallholder coffee supply chains).

From these experiments we developed our basic quality-conditional contract that now rests at the centre of our program. This contract is, effectively a pass/fail contract:

If your coffee passes our quality assessment test we will offer to buy it at a premium, up-front, cash value

If your coffee fails we will show you why it failed and encourage you to come back another day but will not offer to buy the coffee

Our next step was to be able to implement this quality conditional contract in an actual supply chain in a way that ensured quality assessments were low cost, transparent, and robust. For this we turned to sampling theory with a dash of imagination.

Sampling theory is a broad set of theory that relates the reliability with which samples (subsets of a population) reflect the characteristics of interest in the population. We used concepts in this to trial sampling regimes seeking an outcome that:

Allowed us to sample a very small portion of the total coffee lot (cost effective)

Assess this sample in a way that was transparent (for capability building and trust)

To ensure that this sample was highly robust in that it reflected the overall quality of the whole coffee lot being submitted for consideration with a high degree of accuracy

After some testing we landed on a sampling approach that was very cost effective (a small sample) and that had very high reliability up to the limit of our expected coffee submission (around 150-200kg). This was (very briefly):

Remove the coffee from its bag and place on a sheet/platform that allows the tester to vigorously mix the coffee lot. This ensures that the coffee is evenly mixed so that a sample should be highly representative

Sample from the coffee lot using a small standardised container

Score ‘bad’:

Count only ‘black’ category berries and ‘yellow’ category berries. Black category berries score 2 points, yellow score 1.

If the score hits 20 the lot fails the quality assessment test.

By creating a negative score we further reduced the costs of assessment by focusing on the smaller set of failure-generating items and because these ‘stand out’ more in a visual sense.

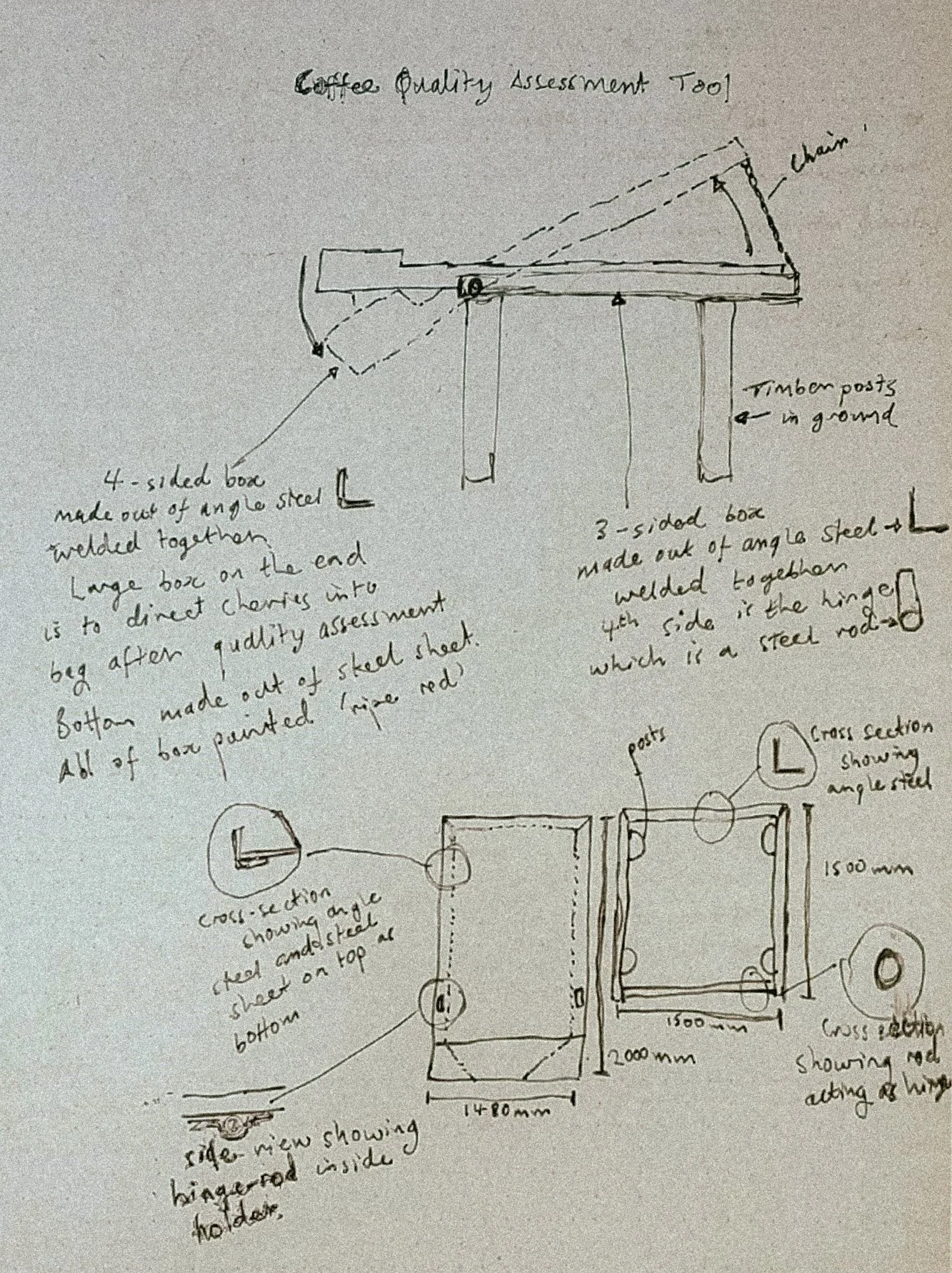

Our final need was to be able to implement this assessment program in a highly efficient and standardised way that also minimised introducing contaminants into the coffee that can affect flavour. We drew up a concept of our first ‘quality assessment table’ (QAT) and took that to a local fabricator. The design of this was based on our experience up to that time in the core costs and issues in assessing fresh coffee quality. The drawing below is the actual drawing we developed and took to the local fabricator.

The QAT is basically a platform box table with short sides, a hinge and funnel at one end, painted red. Pouring coffee onto it we could mix the coffee, sample, and then rapidly pour the coffee back into the bag it came in. So the process ends up being:

A prospective coffee seller arrives.

We pour their coffee bag (up to 150kg at a time) onto the table.

We mix the coffee berries so that they are uniformly mixed. We can immediately get a general idea of quality as the red-painted table helps to identify general patterns of frequency of non-target colours in the berries

We sample using our sample container.

Score bad - 1 point for ‘yellow’, 2 points for ‘black’ type cherries

Pour the coffee back into the bag

If the lot passes we weigh the coffee and offer a sale contract that is entirely voluntary and non-binding for future decisions

If the lot fails we explain the failure mechanism and suggest they come with a small lot again until they are confident they can pass with a larger lot (i.e. lower their effort risk and grow ability to learn)

This whole process takes less than five minutes typically (not including chit chat!). This is far more efficient than any current quality assessment mechanism we’ve come across (and far more robust).

Tying these things together gave us the kernel of an inclusive, high-value coffee supply program. Next, incorporating mechanisms to enable scaling! (see here for our research and implementation of scaling mechanisms – digitisation in payment and quality assurance).